moveurope! Interview series - What does (im)mobility in Europe mean to you?

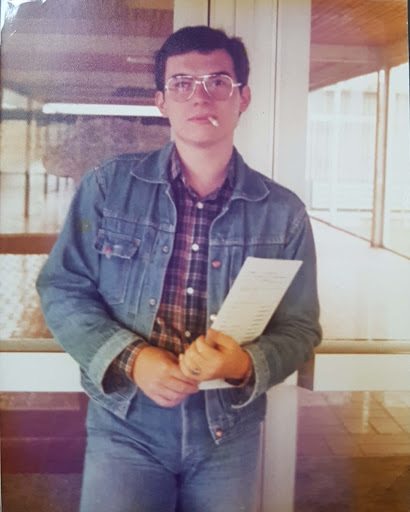

Father of Karla Kästner (director of migration_miteinander), came as a late repatriate with his family from Romania to Germany in the 1970s.

The family applied for asylum because they no longer wanted to live in Romania due to the Ceausescu dictatorship. In our interview, you will learn how he experienced freedom of movement as a refugee in Europe at that time, what the late repatriates are all about and why he has a completely different name today.

From Refugee passport to World Citizen

Since when are you in Germany and why?

My family and I entered the Federal Republic of Germany as refugees on 05 October 1975.

This was only possible because my father, as a doctor, had been sent to Morocco by the Romanian state since 1967 and was therefore allowed to leave Romania. At that time Romania and Morocco had certain agreements, similar to development aid agreements, just like France and Morocco.

As a Romanian, it was not so easy to leave the country by that time – my father could, thanks to his work in Morocco, and we as his relatives could visit him – of course only for a limited time and with a visa. In 1975, when we were all together in Morocco again, my parents decided not to return to Romania, because their freedom was restricted under the dictatorship; I guess, also the fact that they had been out of the country more often and found out that we children in Romania did not have the best opportunities, e.g. my brother should join the army, pushed them to not return. For me and my brother it was not so easy at that time – we had said goodbye to our school friends before the summer holidays and were looking forward to seeing them again afterwards – which never happened again…

My parents then thought about where we could go: we could not stay in Morocco, because otherwise my father and brother would have had to go back to Romania to join the army because of the bilateral agreements (I was still a minor). We thought about emigrating to Canada or the USA, but as asylum seekers we would not have been allowed to work there directly. Since my paternal great-grandfather was a seven-citizen, we decided to go to Germany because we had certain advantages, such as direct access to the labour market.

Who are Transylvanians?

Transylvania is the name given to Germans who, from the 12th century onwards, followed the Hungarian king’s call for colonisation and settled in Transylvania in order to resettle and cultivate the areas there. Thus my father comes from a village that was then administered by Germans. The grandfather had a German name before his wedding, Kondra. In that village there were Romanians, Germans, Hungarians. That’s why my father knew some German. In Germany, the Transylvanians are also called Spätaussiedler. All Spätaussiedler had to register in Friedland, in Hesse, at that time – so did my parents. Normally the usual Spätaussiedler go there directly, i.e. Russian Germans, Volga Germans, Transylvanian Saxons etc. It was also usual for Germany to “buy back” its citizens, i.e. Romania, for example, says: we are prepared to give you 200 Swabians, each one costs 20,000 marks – and then Germany “bought them back”, because these are Germans who belong to Germany, even if they emigrated centuries ago. The same happens, for example, with Israel and Jews in Eritrea or Morocco. These people are always welcome, as workers, as taxpayers…whatever – because they belong to it.

With us it was different back then: we entered the country on our own and got a flat one day after our arrival through contacts and one month later my father started working; nevertheless we also had to register in Friedland to be able to apply for asylum. Normally, as a Transylvanian citizen you get a protection status in Germany relatively quickly. Unfortunately, our asylum procedure took longer than we thought, because we had a bad lawyer who was more interested in our money than in the positive outcome of our asylum application.

What did freedom of movement mean to you back then? Did you feel freer in Germany than in Romania?

I felt free everywhere, because I didn’t have much trouble with the authorities when I was a young person in Romania. My parents were restricted in Romania. However, thanks to my father’s work in Morocco, we as a family always had the privilege of being able to leave the country. As a child or teenager I travelled several times with my mother and brother to Morocco to visit my father – once by plane and otherwise always by car or bus. Once we drove from Romania to Morocco through the whole of Europe… When we were in Germany, we could no longer travel or go wherever we wanted. For example, I wanted to go to France to study after my A-levels – which was not possible at that time. That haunts me to this day, because I thought I was free then – but I wasn’t free to move wherever I wanted, just like people today.

What was it like when you wanted to go to France for your studies but couldn’t go?

After we arrived in Germany, I was 17 and should go to school. At that time I went directly to the French teacher at school and asked if I could go into different classes like a “guest student” to get to know the school and the students. Unfortunately, this was not possible of course, I had to learn German first and should first take a Goethe certificate so that I could communicate at all. So my brother and I went to Haselroth – also on the advice of friends. This is a special school for late repatriates who don’t speak German at all. It was especially meant for those who arrived in Friedland. All different age groups and nationalities were represented there, you could also live, eat and learn German there – but you had to pay for everything yourself, which nobody told us at the beginning. So we went to a special school there and learned Polish and Russian (laughs) – German was a lesson all day long.

When I wanted to study medicine after my Abitur, it was difficult in Germany because of the numerus clausus. Since I felt closer to France and the French language anyway, I wanted to go to France, applied for a job and even got accepted. The French would have let me in too, but not to study, only for tourism; I was living in Germany at the time and had a foreigner’s passport, but I was still Romanian. So at that time they wanted to avoid me coming to France, enrolling again and again, but having no money and being on the French state’s pocket at some point… So France demanded proof back then that the Romanian embassy was responsible for me – and of course I didn’t want that, because I didn’t want to have anything to do with the Romanian authorities – so I couldn’t go. We knew that the Romanian authorities had informers everywhere. It was not possible to make free phone calls at that time, all international connections to Romania were being bugged by the government at that time. There was for example the Radio Free Europe in Munich at that time, where there was always a program with music on Sundays, which was presented by a Romanian speaker, who often criticized the government in Romania and was for more freedom – and lo and behold, until today one does not know who killed him with a knife on the parking lot…

After I could not go to France to study, I went to the Academic Foreign Service in Germany and applied for a training position in medicine. Before that I had applied to all universities in Germany, unfortunately without success. So I first studied computer science in Darmstadt, then I applied again for medicine via the Akademischer Auslandsdienst and immediately got the place in Tübingen. At that time, it was like a quota for foreigners: there was a place to study medicine for foreigners in Tübingen – and I got it, that was great luck.

What is a foreigner’s passport?

The passport for foreigners from that time is similar to the refugee passport today. We were only allowed to travel to other countries for tourism. My first trip out of Germany (me by plane, my brother by bus) was to Lloret de Mar (Spain) after finishing school. We wanted to go with our senior class at that time, but they went to Berlin and I couldn’t travel in or through the GDR, because the risk of being taken to Romania was too high, since I was still Romanian.

And because you weren’t allowed to go everywhere with the foreigner passport, did you get a World Citizen Passport?

At that time there was a worldwide movement that advocated that all people in this world should be equal and have the same rights, against nation states and borders. They were for a world state with world citizens with equal rights. That’s how the World Citizen’s Passport came into being – you could order it online for 100 dollars or something like that. There is also the Nansen Pass, but it is only for stateless people, i.e. people who have been deprived of their citizenship.

At that time I thought: if I don’t get the German citizenship, but I don’t want to keep the Romanian one either, what then? So I ordered the World Citizen Passport – however, this is not an official identification document, with it you will probably be laughed at the border (laughs), but I never tried it…

Today your German passport shows a name that originally is not your real name, is that right?

Yes. When I and my wife got married in Germany in the 90s, we first took my name. Unfortunately, we had various problems because of the name, for example when looking for an apartment, and it was always a tour de force with authorities, in shops, no matter where: nobody knew how to write our name, nobody could pronounce it. When I got German citizenship, I had the unique opportunity to change my name – and that’s what I did. By the way, the name I adopted here in Germany comes from my brother’s wife by marriage – so it doesn’t really have anything to do with us, but we were able to take it at that time, because that was also my brother’s name. My old name does no longer exists – at least not on paper. But it does in me. After so many years in Germany I can say that I am a person without identity – I don’t feel like a German nore Romanian.

Thanks a lot for this very informative interview!

Like what we do? Share with your friends: